~ 7 min read

The Decision Machine: How to Design Your Startup Board

Everything You Know in 5 Min or Less

In one of my early sales calls for Bosware, a Founder/CEO asked me one of the best questions I’ve heard:

In 5min or less, what are the most important Qualitative and Quantitative things you’ve learned about Boards in your career?

I can’t recall my exact response, though it centered around decision making. Evidently, it was good enough since he signed up (and renewed a year later).

But I felt like the question deserved a deeper answer.

That’s how I came to the view that Boards are Decision Machines (Qualitative) capable of delivering 500x more value if they are run well (Quantitative).

Decisions: The Atomic Unit of Startup Boards

As someone setting up or managing a Startup Board, you need to have a point of view on what a Board is and should do.

How you design your Board, run your Board, or make software for your Board - it all stems from your definition of the Board.

Now, most practicioners tend to think of Boards as something like: a group of people that serve the [Company | Founder | Shareholder] and combine helping the company (or at least not hurting it) with some basic oversight.

Long story short, here at Bosware, we came to a different take: Boards are the ultimate Decision Machine for the corporation and their atomic unit of measurement is the Decision.

Good Frameworks Tell You Something

A good framework should tell you if something is good or not — and most importantly, how to make it better.

This framework does pretty well. In fact, you can measure every Board by this one metric: the cumulative value of the decisions the Board produces.

And here’s the obligatory 2x2 chart you could use to assess any Board:

| Board-Level Decisions… | Few | Many |

|---|---|---|

| Value-Positive | GOOD | GREAT |

| Value-Negative | BAD | TERRIBLE |

Of course, this doesn’t mean the Board can or should actually make all the decisions. In fact, delegating to management - together with thoughtful support, information, and deliberation - is one of the best ways a Board produces decisions.

And the best Startup Board veterans agree. Just ask Reid Hoffman, who spoke on the topic during his Farnum Street cameo, and highlighted the importance of deciding fast and well.

And it’s basically what Annie Duke teaches us about ‘thinking in bets’ over the course of a poker game. And what pretty much every other expert on decision-making tells you to do.

If you’re looking for a useful way to describe Boards, the decision machines framework is a good one.

The Value of Compounding Good Decisions

The next question everyone should be asking is how much better is a Great Board versus just a “Good” one?

How much money are you leaving on the table with a Board that is not running at 100% capacity?

This is the quantified view on Boards that almost nobody even touches.

To answer this question for ourselves, we built the following model. Here’s the high level overview:

Step 1. Scope the System

For simplicity, we bounded our model to just the “board-level” decisions. These include both 1) decisions made by the Board, and 2) decisions made by management in consultation with the Board.

In our experience, Board-level decisions typically included these:

- CEO Selection and Performance

- Strategy and focus of the business

- Management team effectiveness (recruiting, selection, performance, replacement, team dynamics)

- Financial budgeting / group-level capital allocation

- Financing timing / size / scope

- Strategic partnership focus / approach

- M&A decisions

Again, the key here is that the Board is directly involved in evaluating and debating these decisions, even if the CEO/Management might actually make the final call in some cases.

Step 2. Define the Equation

Next, we needed some basic formula to translate Board-level decisions into a value metric. We assume a basic system like this:

- Board spends [X] minutes per meeting / year on strategic topic

- …which results in [Y] decisions / minute spent

- …with [Z] expected value (e.g. % of Enterprise Value)

- …compounded over 10 years (or whatever period you choose)

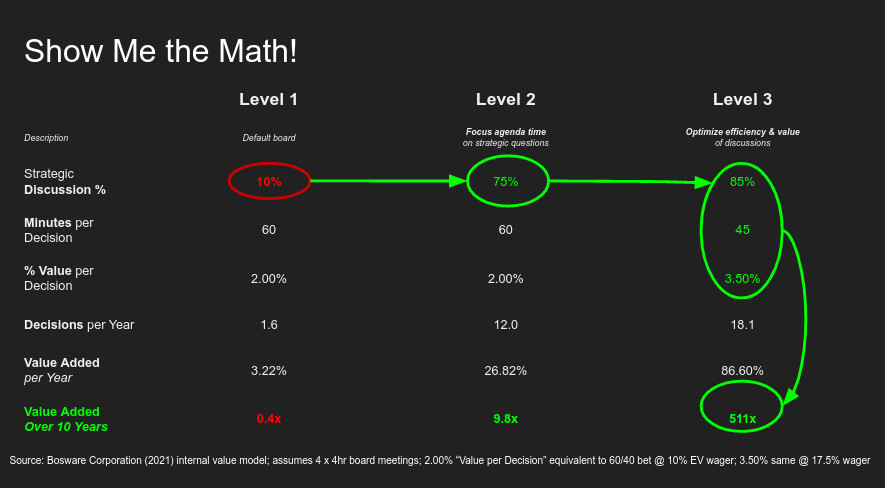

Here is that framework, put to numbers:

You’ll see, we start from “Level 1” which is a ‘Good Board’ baseline from our own direct experience (ie produces decisions that are i) few in number and ii) generally value-positive).

Of course, you could also plot a neutral Board (ie no decisions or neutral-value ones) or even a “Bad” or “Terrible” one. We are just assuming you can get to Level 1 to start.

Step 3. Chart the Results

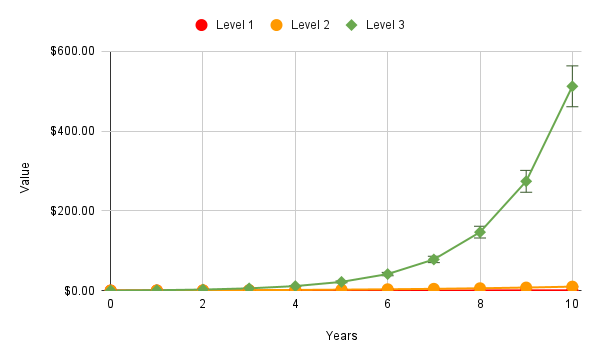

Hopefully you saw the Level 3 Board was 500x better than Level 1.

That’s real money; but it’s not rocket science.

In poker terms, this is like increasing A) your bet size (10% EV to 17.5% EV), and B) the number of bets over a given period of time (from 1.6/yr to 18.1/yr).

And we’re assuming for all levels a 60/40 chance you’re even right (which is about as good as you can do). You are welcome to fiddle around with the numbers - but the point should be clear, there’s big money in something like a Level 3 Board.

Like all compounding machines, running a Level 3 board takes time and repeatability. But over a typical 10-year lifespan of a successful startup (to simplify), the company with a compounding Board Decision Machine converges on untouchable.

Here’s the chart of Level 1-3 Boards over time:

I’m willing to bet most Founders and investors have never thought of Startup Boards in chart form. But now you can.

Why People Don’t Actually Do This

Let’s face it: most Boards are not Level 3 Boards.

Maybe a handful in the venture ecosystem run like this - and likely they got there organically by virtue of the people involved rather than by deliberate design.

But why not? 500x would be worth it to most people.

Like compounding interest, where most Boards get off track is never starting to compound in the first place.

Looking back at interview and survey notes, there were three big blockers to improving Board-level decision making:

- But Why? | Founders/Boards didn’t see or believe in the idea that you can get any value from their Board (or any Board)

- But How? | Improving decision making was nice in theory; but seemed too abstract in practice to implement

- But Who? | With Founders focused on the day-to-day, and VC-directors divided across many boards, nobody had this as priority #1

For now, I’ll just say this: each of these objections are 100% in the realm of “engineering problems” to the motivated builder.

Which reminds me of the old wisdom:

Change is for the people who want it, not who need it.

Go Build Your Decision Machine

Here’s our punchline: if you’re involved in a Startup Board, your #1 priority should be figuring out how to build the abolute best decision machine for the company.

If you want to get started right now - without any further work or money - you could just grab a spreadsheet and keep a log of the board-level decisions your Startup Board produced, together with the approximate value of each. Basically a decision journal. Then just work to improve that series over time.

Of course, we think software can help you do it better. At Bosware, our not-secret-anymore obsession is to understand and build the world’s best Startup Board Decision Machine.

If you’re interested to know more, come check it out: Request a Free Trial

May you decide Fast, Well, and Often, dear friends.